Theme Gender in the Field

The first Lova Photo Competition was organised in May-June 2016 by Reinhilde Sotiria König (anthropologist) and Hanneke van Beek (photographer) in collaboration with Juliette Weegels who took care of the postings on the Lova Facebook page. Reinhilde and Hanneke decided about the theme of Gender in the Field and also acted as the jury.

We made a postcard of the first prize winning picture to distribute at Lova events. An audience award was handed out to the photo which received the most likes from visitors at the Facebook page in June 2016.

Below we present the (slightly revised) report of the jury as published in Lova Journal #35 of December 2016, pp 104-109.

Report of the jury

The jury loves the variation of photographs and stories received. We started out going through all the pictures without reading the stories. All pictures are interesting in one way or the other. And some pictures are absolutely beautiful and perfect in their composition, colour, message, and form. Yet the picture that resonated the most, even without the story, is far from technically perfect.

We are looking beyond the obvious, beyond the conventional and cliché. Whereby the cliché would be the obvious: fatherhood, motherhood, female or male gaze, sexualisation of man- or womanhood.

Our criteria are informal, subjective and unorthodox. Reinhilde looks for a counteroffensive against the clichés World Press Photo (an exhibition at the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam) displays year after year. They expose most of the time black or otherwise as ‘The Other’ by the Western public perceived bodies, or poor bodies in mourning or grief, or the happy or unhappy ‘exotic’ child or woman. Reinhilde’s criteria are: Is there any link with gender or feminist anthropology? Would I like to see this picture along the highway in sky-high proportions without getting miserable of seeing a stereotype or Oxfam message? And, at the same time does the picture touch the content of feminist anthropology as a way of looking at the world crossing the borders of gender binaries and hetero-normative expectations?

Hanneke (aka Photo-coco) looks at photography in an open way: Do I feel why the picture is taken? Does it make me curious? What does the picture do to me, in what way am I touched? What kind of energy vibrates through the picture? Does the picture speak for itself and leave room for interpretation at the same time?

The first prize winning picture of Abu Ahasan that won our hearts was the one with three people melting together on the top of a train. The fast vehicle is not really visible, the trees are flying by and not even the people central in the picture are in focus. The most appealing thing is how the three protagonists look expectantly into the camera and do have a connection with the cameraperson; one can feel this connection as a viewer and it makes us comfortable. As with other pictures one is more the distant spectator who watches a scenario whereby the idea of the maker distanced the viewer from the object within the picture. This is the case with pictures very familiar to anthropologists, where the researcher is engaged in some activity or stands next to the research objects; the idea of being there, having done it (“je fais l’Afrique”), having been emerged in another culture feels somewhat uncomfortable to the contemporary reader of pictures.

Next to our first choice, we were touched by the second prize winning picture of Melissa Chacón of a belly button. A naked pregnant belly with a beaded necklace on top of it, a hand holding the t-shirt up, so that we can see the necklace. It made us curious and we wanted to know more about the story behind this. It has the obvious of being pregnant, but also the hope of maybe being able to protect. It’s beautiful and does not push the message in the face of the beholder. It did not matter if the belly was black, white or yellow, the woman laying there could lay everywhere, America, Russia, Africa, Asia, Polynesia, Europe … it does not matter. The universal idea of wanting to be able to protect the offspring appeals to the viewer. The story behind it makes us curious and we would like to talk to her straight away. We do not know if she herself took the photo or anybody else, but the scene could easy be a pose for a researcher studying pregnancy as an intimate registration of personal hope and care. It does not matter, the transcending power of the picture doesn’t need context.

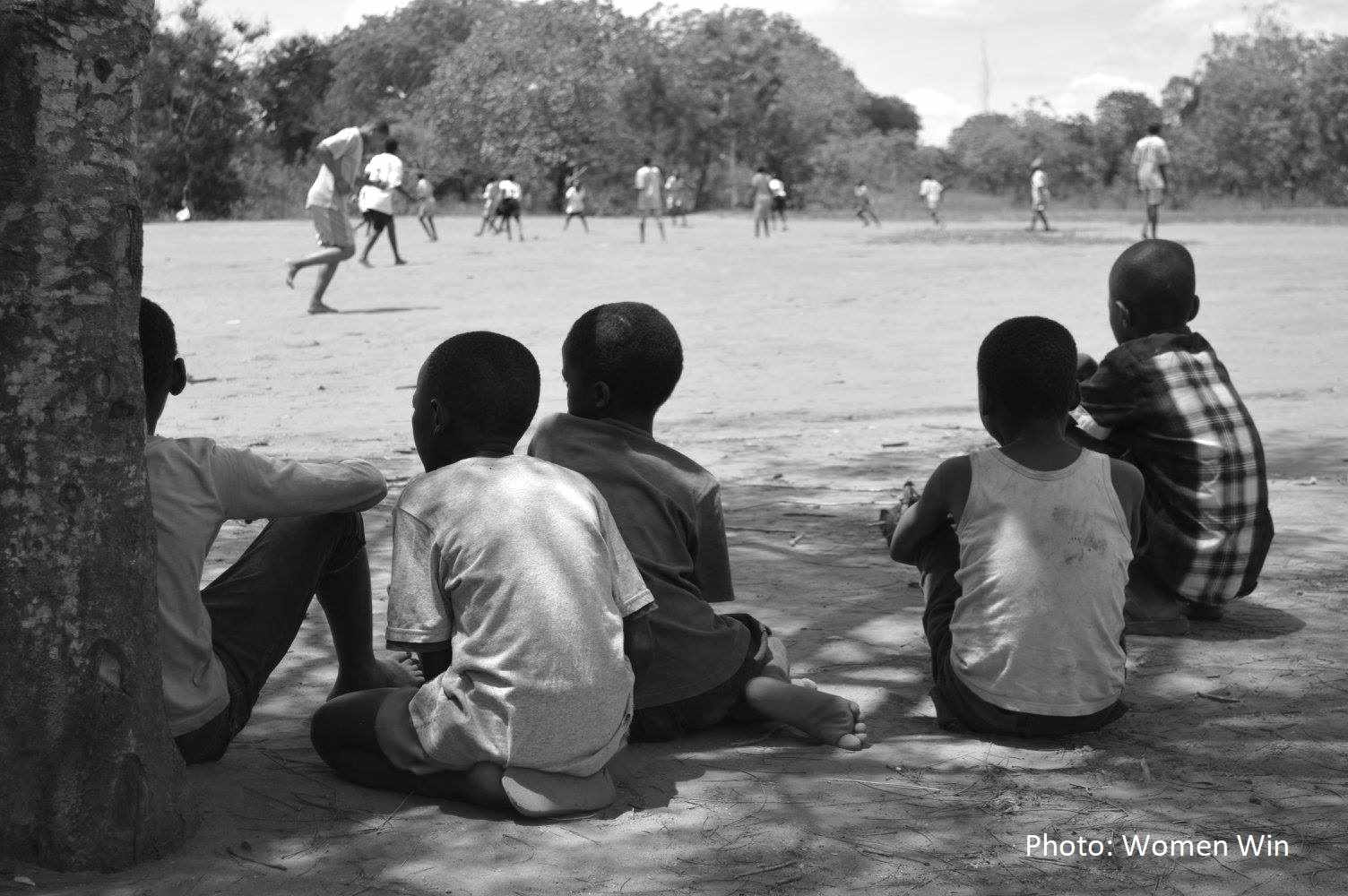

The third prize winning picture of Women Win was picked by Hanneke, who pointed out that the young boys sitting in front of people playing football seemed to show the hope of being big enough one day to be the man on the field. Reinhilde agreed and also liked the composition of the picture very much; the little foot in front, the ball played by people in blue shirts, it has a circle, a circle of live. We realized we couldn’t be sure that the youth in the foreground were actually boys, yet it came as a surprise when we found out that the players were women. Above all one feels the excitement of the children in front and the effort of the players; it does not matter in the end if the players or viewers are male or female.

Therefore our first and third choice meets the criteria of crossing gender binaries borders (‘genderoverschrijdend’ in Dutch). The pictures have a beauty and a subtle message beyond the conventional and raise questions. That we see the back of the children and none of the faces of the players in the third picture clearly makes the viewer to a distant passer by, a voyeur if you wish. No engagement is possible, but the fantasies about what is happening here is wonderfully possible. The openness of the faces in the picture of our first choice, with the three people who emerge as one on the top of something (a train) in contrast, does engage the viewer immediately and makes us part of the story and of picture. The friendly, juvenile, happy faces immediately want a reaction from us. It’s about daring to look: they dare to look in the camera, we dare to look back and we can see the expectations in their faces, and also the anxiety. As the camera person was able to find a connection with those youngsters, it is easy for the viewer to connect without being uncomfortable being part of the scenery. It feels as if you could sit next to all four (three protagonists and the camera person) of them and chat along about hopes of the futures. It helps that the three form a triangle in the middle of a moving object that draws the viewer also to them. It’s a very intimate portrait of three people melting into each other, whereby sexes do not seem to play a role. It’s human. It’s an intimacy together and with the photographer. But it’s mostly a joie de vivre, joy and openness which draw the viewer into it. Maybe we are tired of problems or clichés, maybe we needed these hopeful moments of freshness and friendliness, openness and joyfulness. The pictures celebrate human contact surpassing the rigid frames of gender clichés.

Below we present the pictures and the texts written by the photographers.

First prize winner: Abu Ahasan

PhD candidate at the Institute of Gender Studies, Radboud University, the Netherlands and senior research fellow at Research and Evaluation Division, BRAC, Bangladesh

“Born and bred in Dhaka, I am an anthropologist by training, currently pursuing my PhD research under the supervision of Willy Jansen at the Institute of Gender Studies, Radboud University, the Netherlands. My ethnographic fieldwork involves a group of disenfranchised youths living in an Islamic shrine in Bangladesh, the title of my research: ‘The children of Baba Shah Ali’: Love and Intimacy at the Margins of Dhaka. An understanding of power, life and counter-conduct from the positions of marginality is where my anthropological interest lies. My quest is self-critical, finding a balance between the ways I read the social world and live my life. I took this photo capturing some of my interlocutors – Jhonny (top), Shakil (left), Shoma (right) and Babu (behind) – as we were heading to the festival of Lengta celebrating the death anniversary of a legendary subaltern saint. We were sitting on the top of a train on our way from Dhaka to a southern district. Roof riding, although illegal, is the most common form of long distance travelling for working and street connected young people in Bangladesh. Charity organisations identified this as the leading factor in child deaths in the country. Kids are not naive of risks either, nevertheless, for them roof riding doesn’t cost any money, comes with intense feelings of excitement and freedom, and enables them to become spatially more mobile. This was a one of many new experiences that I gained recently through my fieldwork, which proved to be anthropologically crucial in forging friendship with interlocutors and tasting the sensory experiences of everyday life at the margins.”

Second prize winner: Melissa Chacón

Student of the GEMMA Erasmus Mundus Master’s in Women’s and Gender Studies in Europe at Utrecht University, the Netherlands

“Angy Andrades was a participant in the project of Displaced Affects: Emotional-Embodied-Experiences of Displaced Women in Colombia. This project included oral narratives, life stories as well as visual narratives: participatory photography. Angy (19 years-old) narrates in this picture an object with emotional meaning for her. Angy was abandoned and sent to an orphanage for girls in Bogotá at the age of three. Days after her arrival, one of the nuns in this place gave her this bracelet, and told her to keep it for protection and support. Angy grew up without a constant protection figure, but this object embodied the presence and support that she needed: ‘It reminds me of the good and the bad things that I’ve been through, so it reminds me that people come and go, but my bracelet has been here always, she knows, (laughs) yes she knows what I’ve done right or bad, she has like the positive and negative in me, because she has been with me forever.’ Now Angy is pregnant and she wants to give this bracelet to her baby girl transferring to her all the emotions associated with this object (love, protection, support, strength). This picture embodies one of the emotional resistances that Angy has developed in order to cope with violence, and represents the strength in every woman for building a reparative present despite experiences and memories of vulnerability and social injustice.”

Third prize winner and winner of the Audience Award: Women Win

The NGO Women Win is the global leader in girls’ empowerment through sport.

https://www.womenwin.org/

“We leverage the power of play to help girls build leadership and become better equipped to exercise their rights. Sport is only our tool. Our end game is helping girls thrive as they face the most pressing issues of adolescence, including accessing sexual and reproductive health and rights, addressing gender based violence and achieving economic empowerment. Since 2007, we have impacted the lives of over 1.24 million adolescent girls in over 100 countries. This has been made possible by collaborations with a wide variety of grassroots women’s organizations, corporates, development organizations, sport bodies and government agencies. Our work is strategically positioned at the intersection of development, sport and women’s rights.

The picture is taken in Kilifi, Kenya at the community-based organization Moving the Goalposts (MTG). Women Win decided to submit this picture for the LOVA Photo Competition to show how sport can challenge gender norms. At first glance the gender of the players and spectators is not clear. As football is often considered a traditionally male sport, it is easy to assume the players are boys. However, we think this is a very powerful picture because the players are actually girls, supported by boys watching from the sidelines. The girls are MTG participants taking part in weekly practices, tournaments and on-going leagues. Through MTG’s programmes, adolescent girls are taught key life skills and encouraged to take up leadership roles within the organisation and the wider community. MTG and other Women Win programme partners are shifting gender roles on the field by creating opportunities for girls and young women to play sport and claim traditional male-centric public spaces such as football pitches.”